We concluded our spring lecture series celebrating the work on John Ruskin with a discussion about his enduring influence on the city of Venice, and on the development of the conservation movement world-wide. Here we further explore the SPAB's early and controversial Venice campaign.

John Ruskin’s ideas about building conservation in The Seven Lamps of Architecture and The Stones of Venice were very influential on William Morris and Philip Webb when they founded the SPAB in 1877. They did perhaps not expect that one of the Society’s early controversies would concern St Mark’s Cathedral in Venice. It garnered the Society a lot of publicity – some good, and some bad.

When William Morris returned from a visit to Venice in 1878, he reported to the SPAB’s committee that medieval mosaics were being removed from the baptistery of St Mark’s cathedral. Though the SPAB was founded to protect buildings in Britain, Morris urged the Society to intervene and the SPAB foreign committee was set up in 1879, appointing the artist John Bunney (Ruskin’s former pupil at the Holborn Drawing School) as foreign correspondent for Venice.

Architect Giovanni Battista Meduna had been leading restoration work to St Mark’s for some years. His works on the foundations had successfully halted some dangerous subsidence but also demolished parts of the cathedral and rebuilt the southern facade.

When word reached London of Meduna’s plans for a major restoration of the west front of St Mark’s, Morris urged the committee to put all the Society’s resources towards a campaign to oppose the scheme.

Letters were published in all the national newspapers and Morris spoke at public meetings in Birmingham and Oxford. The SPAB submitted the St Mark’s Memorial to the Italian government, with over 2,000 signatures. The best of the British establishment and intelligentsia were among those who signed, including: famous writers like Browning, Tennyson, Ruskin, Eliot and Carlyle; artists like Rossetti, Watts Leighton and Millais; prominent architects; politicians including Gladstone, Disraeli and 50 MPs; three Dukes and seven Bishops.

Unfortunately, Morris’ passionate but confrontational tone enraged the Italian public, press and politicians, rather than convinced them. No significant effort had been made to enlist support for the campaign in Italy. It was unfortunate that in their excitement to prevent the damage to the cathedral, the committee had not researched the Italian state’s structure and had addressed the Memorial to the wrong government department.

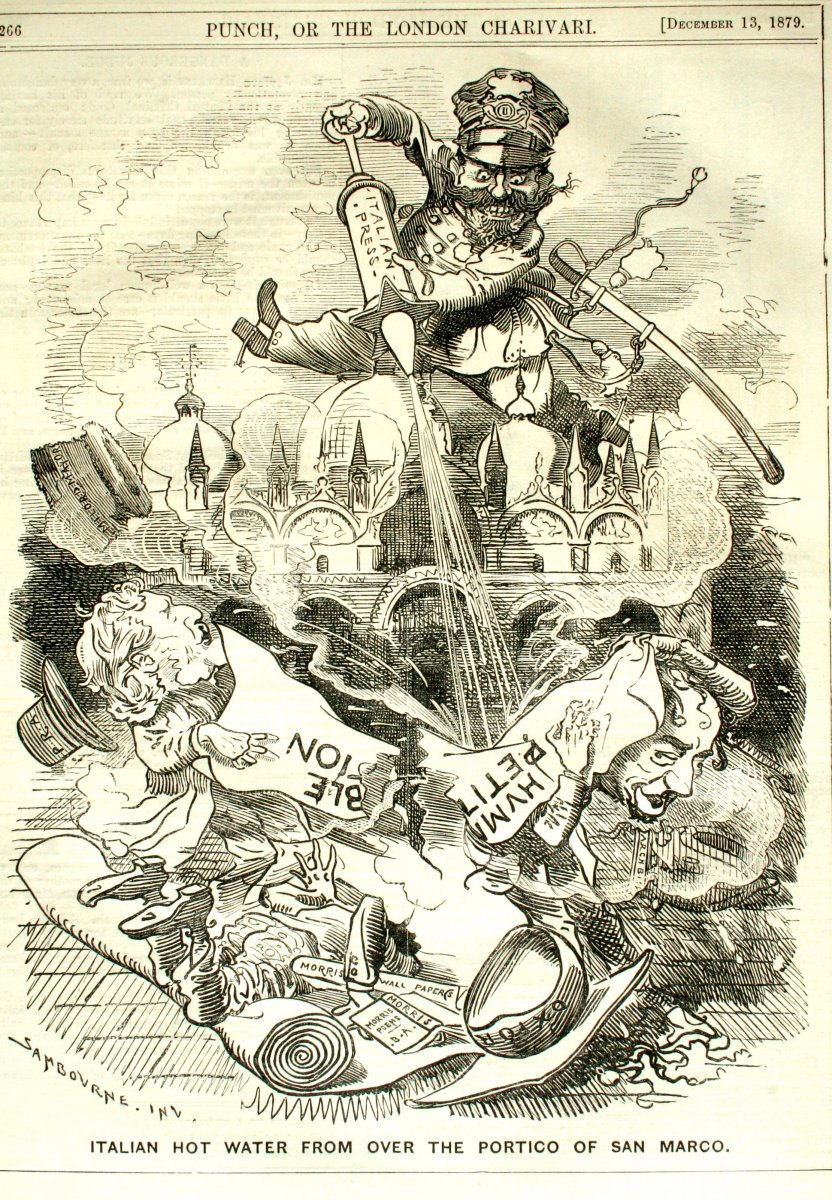

There was also criticism in the British press. These cartoons were drawn by Edward Linley Sambourne and published in Punch, the British satirical magazine. The first, from December 13 1879 shows Lord Leighton, Morris and Disreali cowering under a figure representing the Italian press, dowsing them and their ‘humble petition’ with water (Morris has tripped over his wallpaper and fallen on his face).

The second, dated January 10 1880, shows clowns and jesters dancing around the cathedral, towered over by a winged lion, the symbol of St Mark. It features caricatures of John Ruskin (top-left), Morris, (top-right) and George Edmund Street (below Morris), who had signed the Memorial, even though he had been the subject of the Society’s criticism previously.

Morris and the SPAB quickly made efforts to repair the damage with the Italian authorities and - perhaps due to the publicity from the SPAB’s campaign - in early 1880, the Italian government announced that works to the west front of the cathedral would cease.

Morris and the SPAB learnt an early lesson. The campaign’s haphazard planning had meant that mistakes were made and its whole approach was high-handed. The tone of future SPAB campaigns was more conciliatory, especially concerning those building outside Britain - the baptistery at Ravenna, for example. A separate St Mark’s committee was formed with international members to lobby for the cathedral’s protection in future. Despite the controversy, however, the Venice campaign had made the SPAB better known – if notorious – and provided a platform to put forward the SPAB approach on an international stage. Copies of the cartoons still hang in the Society’s offices today.

Further reading:

From William Morris: Building Conservation and the Arts and Crafts Cult of Authenticity, 1977-1939 ed. Chris Miele, Paull Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and the Yale Centre for British Art, 2005.