Before the mass production of inexpensive portable cameras, artists' sketches, prints and paintings were often the only contemporary record of what are now lost or overly-restored historic buildings – but to what degree can we trust the accuracy of these images?

The primary sources we have are artworks produced on site. These are more likely to be accurate and unedited images, as they were created as a personal, commercial or military record of a building. Drawings of architectural plans are often attractive images in their own right - however possible changes during construction should be taken into account.

Secondary sources are drawings that use the original sketch or memory as reference but may make significant changes to make the artwork more decorative and saleable. Further stages may include the sketch or painting being used as a source to make a print for either publication or display.

A good example of this process is the work of Paul Sandby (1731 - 1809). Sandby was a military draughtsman who became an artist. The accuracy of the detailed drawings in his sketchbooks (at the National Gallery of Scotland) is largely translated to his picturesque large-scale watercolour landscapes. Employed by the Board of Ordinance in the 1740s and then appointed as chief draughtsman to the Military Survey in Scotland to make topographical views of the Scottish Highlands. He later taught the architect Robert Adams, and in 1768 became a founding member of the Royal Academy, London.

Paul Sanby, An Unfinished View of the West Gate, Canterbury, 1780-1785, Pen and brown ink and oil on paper, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Professional-level skills were required by the draughtsmen, architects and artists who were needed to design, record or map buildings or estates. Sometimes incidental details included just for local colour, such as the craftsmen shown at work, are now an interesting record of contemporary building practices. 18th-century topographical prints that showed a basically accurate but homogenised image of country houses were popular but can be idealised images, as their function was display the landlord’s ownership and taste.

Amateur sketches may therefore be a more accurate representation. This Victorian pencil sketch (below) of Kirkstall Abbey, in West Yorkshire shows an accurate view from the South-East, though the foreground appears to have been romanticised. It is possible the various elements were combined as a drawing exercise by a Victorian woman.

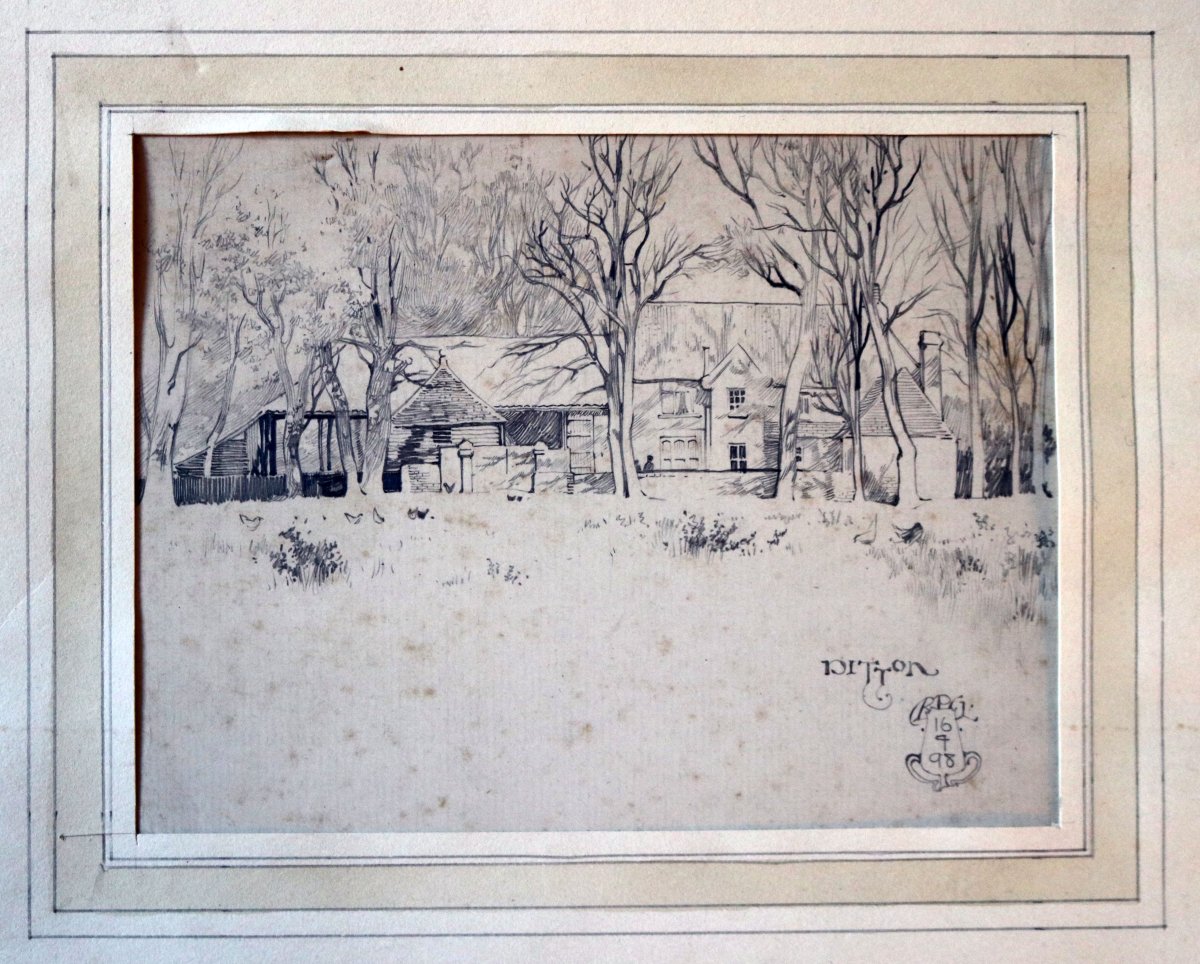

By comparison this 1898 pencil sketch (below) of a farmhouse and barns in Ditton by ‘RPG’ has the feel of a sketch done on location. The building isn’t an important one, the viewpoint is domestic, but if it can be identified, it is a useful record of a vernacular type of building that is often lost or heavily altered.

Artists can also deliberately use a certain amount of abstraction to produce a sense of place and atmosphere, rather than aim for a strictly representational drawing. This lithograph by John Piper, of the church at Inglesham in Wiltshire, includes accurate details but combines several viewpoints and expressive colours. It was made in tribute to his friend John Betjeman, poet and SPAB committee member - according to Piper, Inglesham was Betjeman’s favourite church.

In summary, providing the context and historical filter of an artwork is taken into account, it can be a useful resource for the study of buildings. If the artwork is the only existing image of a lost or over restored building however it is important to assess the degree of probable accuracy and any changes the artist may have made for effect.

John Piper, Inglesham church, Lithograph, 1989. Limited edition prints are available.