Stonehenge may have an air of timelessness, in fact it has been a place of constant change, as our archive reveals...

Stonehenge is considered by many to be England's greatest historic monument. The circle stands at the centre of a World Heritage Site and is part of a wider prehistoric ceremonial landscape. The site is managed by English Heritage and much of the surrounding land is in the care of the National Trust.

CC BY-SA 4.0 / TobyEditor

During the summer and winter solstices free access to the circle is still allowed to those who attach to it a spiritual importance, but 21st-century management of the site as a major international tourist attraction has undoubtedly removed from Stonehenge some of the magic it held for 19th century visitors. Then, visiting was largely uncontrolled, but as long ago as 1900 the debate about freedom of access versus conservation needs was already underway. This issue of access versus conservation perhaps had its most violent expression in the mid 1980s, when the ending of the Stonehenge free festival led to the notorious ‘Battle of the Bean Field’ between police and festival-goers, but the seeds of this confrontation had been sown many years before.

Today, Stonehenge is generally treated as an archaeological treasure. Its importance as an element within an extraordinary archaeological landscape has been increasingly understood, but in its own right it is simply the ruin of a structure. Early members of the SPAB viewed it in these structural terms and approached its conservation and repair just as they would a ruined abbey.

When the Society was founded, Stonehenge was also still very much private property. In 1893 - and despite the Socialist leanings of some of its founders - the Society's public position, in relation to circle, was to “disclaim anything approaching a desire to interfere with the rights of private ownership”. Nevertheless, new possibilities for public acquisition of major historic structures and sites had resulted from the 1882 Ancient Monuments Act. In theory this gave the government's first Inspector of Ancient Monuments, General Pitt Rivers the opportunity to negotiate a transfer of ownership to the state, but as he explained to the Society in a letter of 1889, it had been a “source of constant and unprofitable trouble”. Pitt Rivers was no longer receiving any response to his enquiries from the owner and his frustration and concern for the stones showed: “I am myself against compulsory measures as a rule, but I am of the opinion that such powers should exist, and should be applied only in rare cases in which the neglect of important monuments amounts to national disgrace”. within the emerging conservation movement there was a conflicting fear that unmanaged public access was leading to disastrous decay.

Stonehenge in snow. Credit: English Heritage

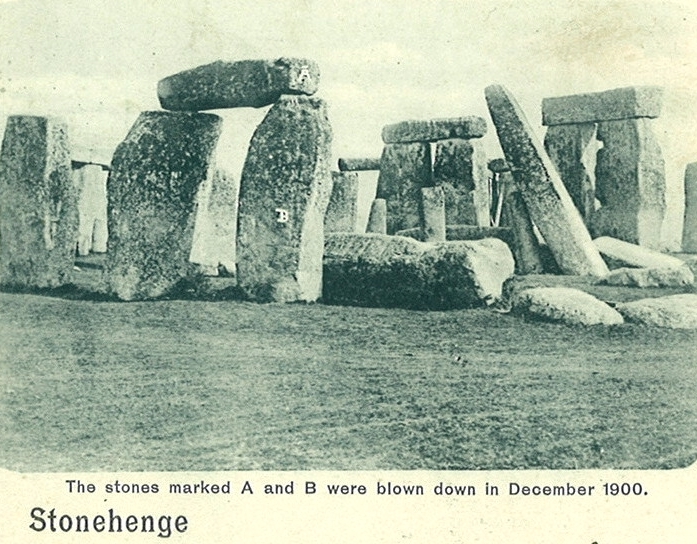

The crunch moment came at the very end of 1900. On the last night of that year, an upright and lintel fell - the first time a collapse of this kind had happened for over a century. In its aftermath, debate raged about its causes. General Pitt-Rivers had predicted that rabbit burrows would undermine the stones, but in 1900 workers constructing a railway close to Stonehenge (now removed) were seen by many as the likely culprits. more plausibly, others observed that for years the volume of foot traffic had been steadily eroding and compacting the soil at the stones' base. Combined with bad weather this gradual deterioration of ground conditions seems the collapse's most likely cause.

What was to be done? A crisis point had been reached: serious decay was occurring and the monument remained in private hands. In February 1901, eminent archaeologist, Prof Flinders Petrie, wrote to The Times in a piece that was notable for its SPAB-mindedness: “ We have rather a terror of “Restoration” thanks to Mr Ruskin’s energetic exposures of the crimes that have been committed in its name… and it is Restoration as well as safe-keeping that some demand for Stonehenge.... There is [fortunately] no longer any fear of the whole thing being shipped off bodily to America…”

As well as debate, the first two months of 1901 saw action. Urged on by the youthful National Trust, the SPAB prompted the Society of Antiquaries to form a committee that would advise on the monument's future care. Secretary Hugh Thackeray Turner stood against any “general replacing of stones…” He took a personal lead in the matter, putting himself forward with John Carruthers – a Socialist engineer who had accompanied William Morris on his last trip abroad - for the Society of Antiquaries’ new Stonehenge Committee. The SPAB also turned to its most trusted technical adviser, Philip Webb, for advice. . He felt that the underpinning of unstable stones on a concrete foundation offered the best option. This was adopted as the Society’s preferred approach, along with re-erecting the two stones that had fallen on New Year's Eve. This was not motivated by a desire to Restore but because it would achieve a more satisfactory repair. One of the stones had suffered fissures during collapse and these could be pinned and conserved most effectively if the stone was re-righted. This argument was accepted by the Times which reported, on 23 April 1901, that the “two grave flaws” in the fallen stone “when placed upright these will matter little, but if the stone is left inclined the effect of rain-water freezing will before long break off the upper third part of the stone.” There was no wish at the SPAB to see reinstatement of other recumbent stones. Thackeray Turner expressed a “determination to do as little as possible in order to save the monument for posterity”.

Philip Webb and the Society were also drawn into the highly-charged debate about site’s management. Webb had considered the possibility constructing a “sunk fence” or ha-ha “…it seems to me that if it is necessary to put a security fence round the area of the stones a sunk fence would be the only bearable one... Some years ago I thought of this fence, knowing the rudeness and brutality of British civilization – which would probably make it necessary. If the fence at any time should be done it should not take the circular form of the stones...” The SPAB’s sole motivation was improvement to the protection of the stones, but in supporting the idea of enclosure it fell in line with the wishes of the owner, Sir Edmund Antrobus of Amesbury Abbey. The stones’ protection no doubt motivated Antrobus too, but some feared he was using the issue to emphasise his private ownership, restrict public access, and raise revenue from authorised visitors

When enclosure was carried out, and proved to be a barbed wire fence rather than the sunken ha-ha which Webb had favoured, the indignation of leading figures at the newly-formed National Trust was great. Founder Canon Rawnsley was particularly scathing. Writing to Turner in an aggravated hand, he said of those who had seen the fence and thought it acceptable: “I can only suppose they left their eyes behind them”. There was no doubt that the Society agreed in principle. Turner wrote “my personal wish is that Stonehenge should be the property of the nation (or the National Trust by preference) and that it should be properly repaired”. Local feelings were similar, with the people of Amesbury demonstrating against Antrobus’s enclosure and his introduction of an entrance charge.

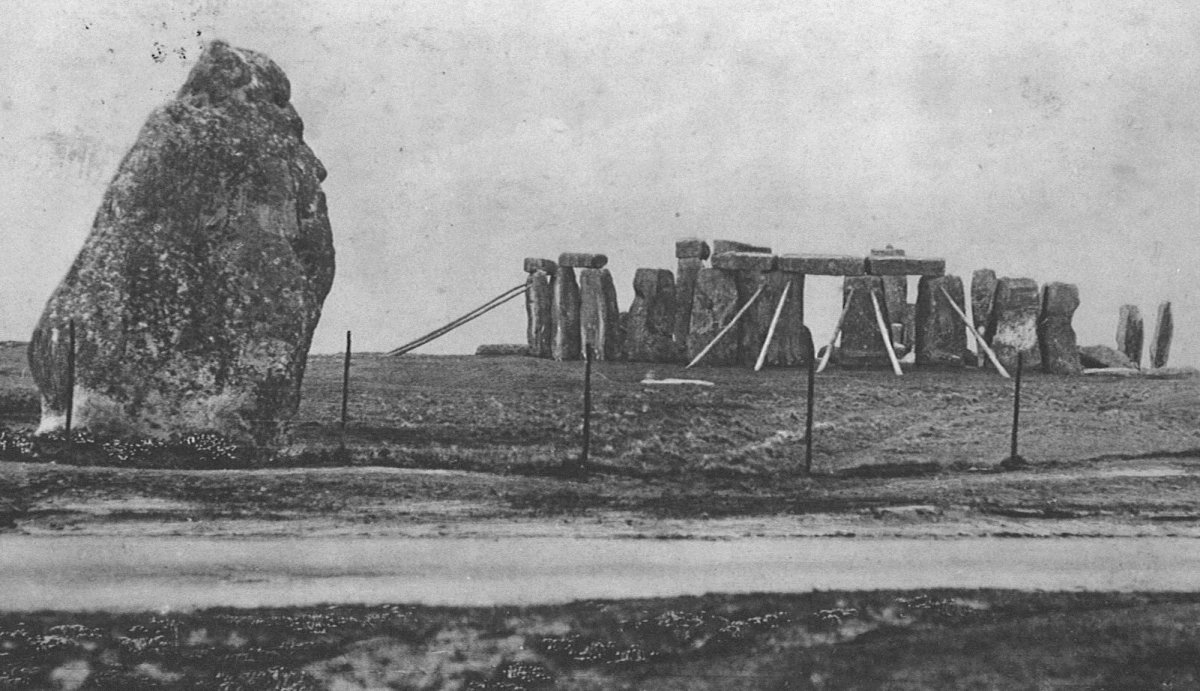

In 1916, showing props and fencing. Credit: SPAB Archive

The underpinning, repair and re-erection of the fallen upright, with accompanying archaeological excavation, was ultimately put into effect under the technical supervision of SPAB committee member Detmar Blow and John Carruthers. Blow wrote in 1902 "A strong cradle of 12-inch square baulks of timber was bolted round the stone, with packing and felt, to prevent any marking of the stone. To the cradle were fixed two 1-inch steel eyebolts to receive the blocks for two six-folds of 6-inch ropes. These were secured and wound on to two strong winches fifty feet away, with four men at each winch. When the ropes were thoroughly tight, the first excavation was made as the stone was raised on its west side." Concern about the stability of other Stones remained, and in 1902 the SPAB and Stonehenge Committee advised the introduction of wooden props to prevent further collapses.

1901 excavations. Credit: Wiltshire Museum, Devizes

A conclusion to the public ownership debate was finally reached in 1915 when the Stonehenge site was bought by Sir Cecil Chubb and passed to the nation in the following year. It took until 1927 before the wider landscape could be acquired by the National Trust through mass public subscription Further stones were re-righted in the 1920s, 1950s and 1960s.

The changes to visitor management over the last century are perhaps an inevitable consequence of the ever-increasing public interest in the stones; the reasons for the extent of Restoration that has occurred are more debatable.

by Matthew Slocombe. A longer version of this article appeared in the SPAB Magazine, Summer 2014. The magazine is a benefit of membership. Join us today.