The Festival of Britain was a national exhibition held throughout the UK in the summer of 1951. Originally planned to celebrate the centennial of the Great Exhibition of 1851, the 1951 festival focused entirely on Britain and its achievements. Writer and broadcaster Gillian Darley looked in our archive to explore our involvement...

‘Dear Sir,’ a letter begins to Monica Dance, Secretary of SPAB, on 29th November 1948, the Council for Architecture, Town Planning and Building Research for the Festival hoped that the Society ‘would wish to contribute to the Festival theme in its programmes planned for 1951.’

The emblem designed by Abram Games on the cover of the South Bank Exhibition Guide, public domain

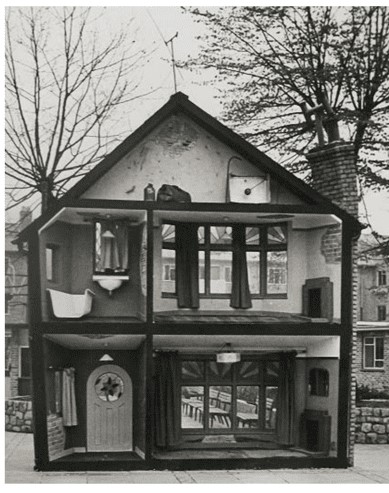

Mrs Dance wrote to the Secretary of the Architectural Association, now in charge of convening further discussion on these topics, to say given that the Society ‘has a lot of information regarding ancient buildings which might be valuable’ and it would like to be included in the Working Party to be convened for the organization of Technical Information Services. This rather prosaic element, to be physically represented in Poplar, East London by the Building Research pavilion was overseen by the Design Group. As John Ratcliff, Deputy Director, Architecture and Deputy Controller, Construction wrote later (in Mary Banham and Bevis Hillier’s 1976 invaluable volume A Tonic to the Nation) ‘the problem was how to make these indigestible subjects palatable.’ Dozens of unlikely bedfellows were being herded, committee session and working party meeting at a time, towards a result which can have satisfied none of them. Ratcliff designed the research pavilion as a jerry-built semi, nicknamed Gremlin Grange, ‘a series of boxes’ exemplifying all the faults and failures that could be found in construction.

Gremlin Grange, a scaled-down version of an inter-war semi-detached house, showing how many things might go wrong when scientific principles were ignored. It stood on the Lansbury Estate in Poplar, built as a 'live architecture exhibition', intended to showcase Britain's post-war reconstruction.Credit: the National Archives

But in 1949 hopes were higher for the conservation sector. And the authorities now addressed Monica Dance as ‘Dear Madam’. In June an invitation came for the SPAB to appoint a representative on the first working party, alongside the RIBA, the Institution of Electrical Engineers, the Institution of Heating and Ventilation Engineers, the International Federation of Housing and Town Planning and the Building Research Station. The invited parties were, it is fair to say, a bran-tub of random professional bodies into which the SPAB scarcely was a natural fit. A month later, it appears that an International Conference on Building Research was proposed, but appears to include no ‘item of research in which the Society could cooperate although it believes that its knowledge of traditional methods might provide an interesting and useful aspect’. Nor, Monica Dance adds, could the Society, as a voluntary body, offer much towards the intended guarantee fund.

By April the professional institutions had prevailed. Mrs Dance was left to respond to the National Association of Parish Councils, gently reminding them that worthwhile as renovation and repair of buildings might be, it must be vested in those with ‘expert knowledge’. Meanwhile the SPAB had to deal with letters flowing in, exemplified by a request for advice for the historical pageant planned in Diss, the scriptwriter seeking authority to date at least two rooms at the Saracens Head to the time of the Crusades?

Credit: SPAB Archive

Over the subsequent months and the SPAB contribution to official Festival affairs had been whittled down. It was reduced to some five photographs to be included in the National Trust exhibition, expensive prints for which the Society was asked to pay. To add insult to injury, Monica Dance wrote miserably, ‘the caption for the picture of Ludlow has been put on Tewkesbury Abbey and vice versa.’

As the SPAB links to the Festival of Britain plans descended into farce, the only area in which they could seemingly still help was with advice, the kind of casework that was relatively routine. Thus, in March 1951, Essex County Council allocated £500 for the restoration of Finchingfield Guildhall, awarded ‘on the basis of your architects report… we hope to get the job completed in time for the ‘Three Village Festival’ there in July.’ In April, Mrs Dance wrote carefully to Lt. Col Sir John Ruggles-Brise, Bt., OBE, (from 1958 the Lord Lieutenant of Essex) to enquire about progress on the Guildhall and the village almshouses. The Society was anxious that the latter, ‘fundamentally in good order’ and thus only requiring ‘localised repair and redecoration’ should not be subjected to ‘unnecessarily drastic work’. She, again, wondered if the SPAB’s architect member could advise further? This elicited a reply from Sir John who, while acknowledging that his survey had been ‘most useful’, had to report that the County Council had elected to ‘employ their own Architect who is on the spot, rather than yours from London.’ After full discussion, ‘I am afraid it was decided… in favour of their own local man, who, of course, is also an expert on old buildings.’

Finchingfield Guildhall, Essex in recent times / CC BY-SA 2.0 / Oxyman

In Great Bardfield, another of the three Festival villages, an influential local farmer decided to demolish the smaller of two handsome barns in the centre of the village. He wrote in self-defence to say that he was an enthusiastic adherent of William Morris’s views on old buildings and that they were misinformed. However, the SPAB eyes on the spot were those of John Aldington, one of the group of artists who lived in and around the village, and he had the foresight to sketch the half destroyed ‘small’ barn and send the drawing to Monica Dance where it has languished, unnoticed ever since. It was 1952. Perhaps Mr Smith, the owner, had decided to wait a year.

Drawing of Great Lodge, at Great Bardfield, Essex in 1952 by John Aldington. Credit: SPAB Archive

Gillian Darley’s 'Excellent Essex' is out now in paperback.

The SPAB archive is one of the oldest collections of material wholly dedicated to buildings conservation. Read more about our archive and search the online catalogue.