On the 110th anniversary of the Ancient Monuments Consolidation and Amendments Act, we look at how the threat to Tattershall Castle helped to bring about some of the first real protections for ancient buildings.

When the SPAB was set up in 1877, there was no legislation to protect old buildings in the UK.

That changed with the introduction of the Ancient Monuments Protection Act in 1882, the first of many pieces of legislation with the aim of protecting our built heritage. However, it covered just 68 sites, mostly pre-historic monuments like Stonehenge, and lacked any real teeth.

At the time, there was opposition to what was seen as the state interfering with private ownership.This legislative move was attacked in Parliament as “an invasion of the rights of property… in order to gratify the antiquarian tastes of the few at the public expense”.

But the tides would start to change in just a few years – spurred on by the scandalous removal of some fireplaces.

Tattershall castle, Lincolnshire.

Tattershall Castle

Tattershall Castle is a moated 15th century red-brick castle in Lincolnshire. Badly damaged in the Civil War, it was abandoned in 1693 and fell into disrepair.

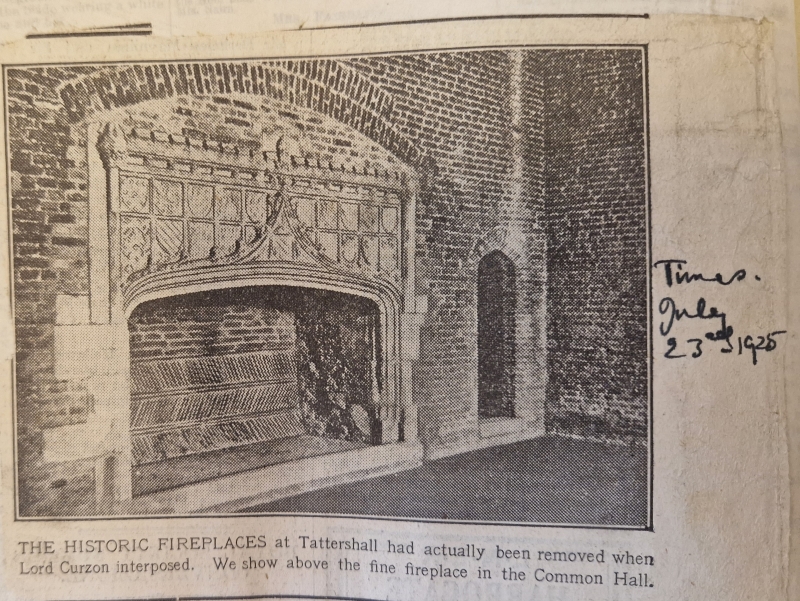

The ruined castle was sold to an American consortium in 1910. The following year, the 15th century fireplaces were ripped out and sold to an American millionaire.

The removal of these medieval fireplaces triggered public outcry. One paper stated, “Tattershall Castle is being ravaged in a time of peace with the consent of its owner and apparently without the possibility of more than verbal opposition.”

A newspaper cutting from 1911. SPAB Archive.

Rumours soon spread that the entire castle would be torn down and rebuilt overseas – a fate that met many European historic buildings and structures in the 20th century, including London Bridge in 1968.

After much outcry and a nationwide hunt, the fireplaces were found in London (possibly on their way to America), purchased by the controversial Earl of Curzon, and brought home to Tattershall.

Curzon purchased the castle for £500 and employed Architect William Weir, who worked closely with the SPAB, to oversee the repairs.

The SPAB Annual Report for 1912 states, “The fate of this most valuable example of a 15th century castle has been watched with anxiety for some time. Happily, it has now passed into the possession of the Right Hon. Earl Curzon of Kedleston, who is undertaking extensive works of repair which will ensure its future safety.” Curzon would go on to leave the castle to the National Trust.

A newspaper cutting showing the historic fireplaces at Tattershall Castle. SPAB Archive.

The Ancient Monuments Consolidation and Amendments Act

At the time, there was very little legislation in place to protect ancient buildings. But his experience with Tattershall inspired Curzon to support stricter protection laws for historic buildings.

He was instrumental in the passing of the Ancient Monuments Consolidation and Amendments Act which gained Royal Assent on this day in 1913. For the first time, the government had powers to act directly when a historic site was under threat. Landowners could be forced to repair structures or be fined, and unpaid fines could lead to imprisonment.

It was a significant step, but it still left many old buildings without protection; the criteria at the time meant only unoccupied buildings were protected. It wasn’t until after the Second World War that old buildings got greater protection, including the listing system that we know today.

If you work with old buildings and would like to know more about current heritage protection legislation and how to apply it, join our online Repair of Old Buildings Course this autumn.