2021 SPAB Scholar Libby Watts introduces the history and production of plain glass windows...

Since starting the Scholarship we have been introduced to a number of glass specialists. We have not only been taught about the history of glass and its varying methods of production, but we have also come to fully appreciate the contribution plain glass makes to the character of a historic building, even though it's a material that's often overlooked.

Since starting the Scholarship we have been introduced to a number of glass specialists. We have not only been taught about the history of glass and its varying methods of production, but we have also come to fully appreciate the contribution plain glass makes to the character of a historic building, even though it's a material that's often overlooked.

It is now impossible for me to look at an old building with new glass, and not be upset by the intrusiveness of this modern material on the eye.

A brief history

It has only been in the last 400 years that plain glass has been regularly used to glaze window openings. Before the 16th century most domestic window openings were unglazed, they had shutters or were covered in thin sheets of cloth, paper or skin to keep out the weather. The earliest examples are found in high status buildings and were constructed of small panes of glass-known as quarries (made from cylinder glass) and then held together in a lattice of lead strips, called cames. These windows were usually reinforced with iron bars, either in the horizontal (known as saddle bars) or in the vertical (known as stanchions).

As prosperity increased in the Tudor period, windows began to have opening casements, often this would include a wrought iron frame set into stone or timber mullions. These opening casements would have the same leaded glazing, but this would be attached to the casement. Leaded casement windows, Hampton Court. Credit: Libby Watts

In the 17th century everyday house glass was slowly becoming more common. Windows were increasing constructed of timber in the form of casement windows, to start these timber casements still had leaded lattice work. However as the production of crown glass began, panes of glass could become larger and the panes within casement windows could be held in with glazing bars.

The casement window was then replaced in the late-17th century with the sash window. The sash window began life with just a bottom moving section, held in place by pegs or latches, however it gradually became what we recognise today, with cords and a counter balance allowing both sections of the window to move.

Then in the 1770s came the introduction of plate glass, which enabled the pane size of windows to increase, by the end of the 18th century most houses, including small workers cottages would have had sash windows. As we move into the 19th century, glazing bars started to be removed and by the mid- 19th century most windows didn't have glazing bars. Sash windows were still common and to compensate for the lack of glazing bars, horns on sash windows were introduced.

A sash window with large Panes of glass and ‘horns’, Cirencester. Credit: Libby Watts

Slab Glass

Slab glass is the earliest form of window glass and is produced by casting molten glass into moulds on a flat surface.

Cylinder Glass (or Broad glass)

Molten glass is blown and swung to form a cylinder, both ends are cut off and the cylinder is then cut lengthways, reheated and flattened into sheets. The glass is then annealed slowly. Cylinder glass is often easy to identify as it has a distorted, ripple effect across the glass with air bubbles and small imperfections.

Cylinder glass halfway through production, at Jim Budd Workshop. Credit: Libby Watts

Crown Glass

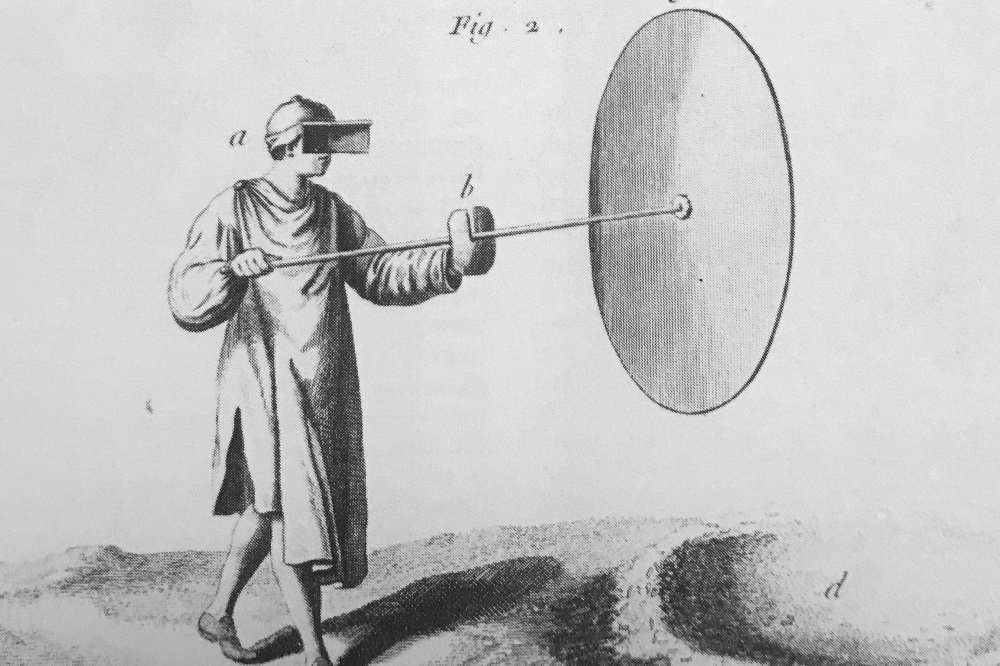

Crown glass was first produced in Europe in the 14th century, however it was not produced in the UK until 1674 and then production ceased in the mid-19th century. Crown glass is produced by molten glass being blown into a bubble and then spun into a disk, historically these disks could reach around 4ft in diameter. The glass is then cooled and cut into panes with the outer areas being the most desired as they were the thinnest. The central bullion or ‘bulls-eye’ where the rod was attached was then waste, however often appears in stained glass or leaded lights as decoration. Although crown glass allowed panes of glass to become larger, it was very expensive, and so leaded glazing remained popular throughout the 17th and much of the 18th centuries.

When trying to identify whether glass is crown glass, one should look for the curved sweeps within the glass, showing the marks of its production.

Crown Glass in production, from Glass and Glass Making, Roger Dodsworth (1984)

Polished Plate Glass

Plate glass was first produced in Britain in 1773. The Chance Brothers industrialised the process in the 1830s, the process involves creating slab glass and then grinding down the surface, before being polished. This enabled the production of high quality relatively inexpensive flat glass. Plate glass allowed the rippled effect to be greatly reduced. The Crystal Palace was built using plate glass in 1851.

Drawn Glass

Drawn glass was invented in the early 20th century in Belgian, and first produced in the UK in 1919. The process essentially draws molten glass upwards, through and over rollers and into a cooling chamber. Drawn glass still has some movement in the vertical plane, as the drawing process is not fully consistent, it is often used to replicate handmade glass in historic buildings.

Float Glass

Float glass was invented by Pilkington in 1959. Float glass is produced by pouring molten glass onto a molten tin surface. The glass ‘floats’ on the tin and as the tin is cooled it creates an even sheet of glass which is perfectly smooth.

Historically the aim of glass manufacture was to produce a product which was as clear and thin as possible, with minimal ripples or imperfections. Pilkington's float glass has enabled us to now have achieved this- therefore one could argue that modern glass is superior to historical glass- however what we have lost within the evolution of glass is the depth and character which glazing once had.

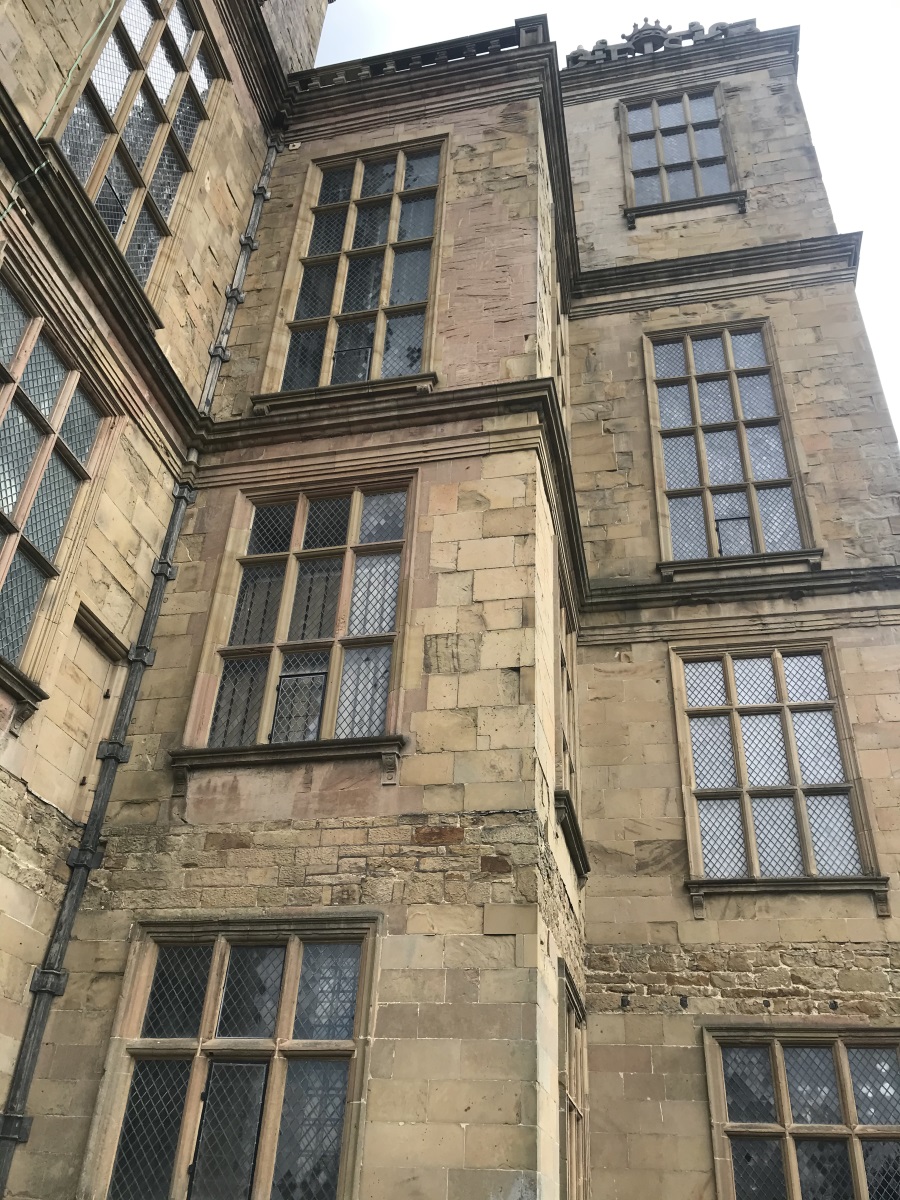

Historic plain glass in quarries, Hardwick Hall. Credit: Libby Watts

Although modern glass maybe suitable for modern buildings, retrofitting this into historic buildings greatly changes the character of the place, and is not in-keeping with the rest of the naturally imperfect vernacular materials.

Next time you look at a historic building, look at the windows - do they glisten in the sun or are they flat? How does this affect the feeling and charm of the overall building? With so many windows being replaced for ‘double glazing’ its time to take a step back and review the beauty of what we have and conserve this wherever possible.

Note: This article is intended as a basic summary and by no means covers all types or styles. Date of windows in images is unknown, but examples are shown to indicate style. Some sources I've found useful

- Dodsworth, Roger. (1984) Glass and Glass Making. UK: Shire Publications Ltd.

- London Crown Glass, Found At: http://londoncrownglass.com/History.html

- Free, Simon (2020) Sash Window Specialists, Found At: https://sashwindowspecialist.com/blog/history-of-window-glass

- Sharman, Jess (2021) The NBS, Found At: https://www.thenbs.com/knowledge/windows-glass-glazing-a-brief-history

By Libby Watts

Could you be a SPAB Scholar? Applications for our 2022 Scholarship close on 12 October 2021. Architects, building surveyors and structural engineers who have completed formal training and have experience working in their field are eligible. Find out more about the SPAB Scholarship and keep up with our 2021 Scholars and Fellows on their journey on Instagram.