Ice house at MunthamCourt / public domain

A lot of thought goes into how best to keep houses warm, especially at this time of year. But in the early 17th century engineers were becoming very interested in how they could keep spaces (and fresh produce) cold.

The answer? Ice houses. Not strictly a new invention (evidence exists of Medieval ‘ice pits’ in Britain) — the new 17th century design was a significant upgrade in terms of insulation.

These new ice houses arrived formally in Britain between 1619-1626, when King James I commissioned the first in Greenwich Park, swiftly followed by a second at Hampton Court.

Designs varied, but the structures were typically cylindrical or conical in shape. Still mostly subterranean, they were now brick-lined, providing strength and most importantly temperature regulation, with thick walls packed with straw or sawdust. A drain would carry melt-water away from the tightly packed ice blocks within.

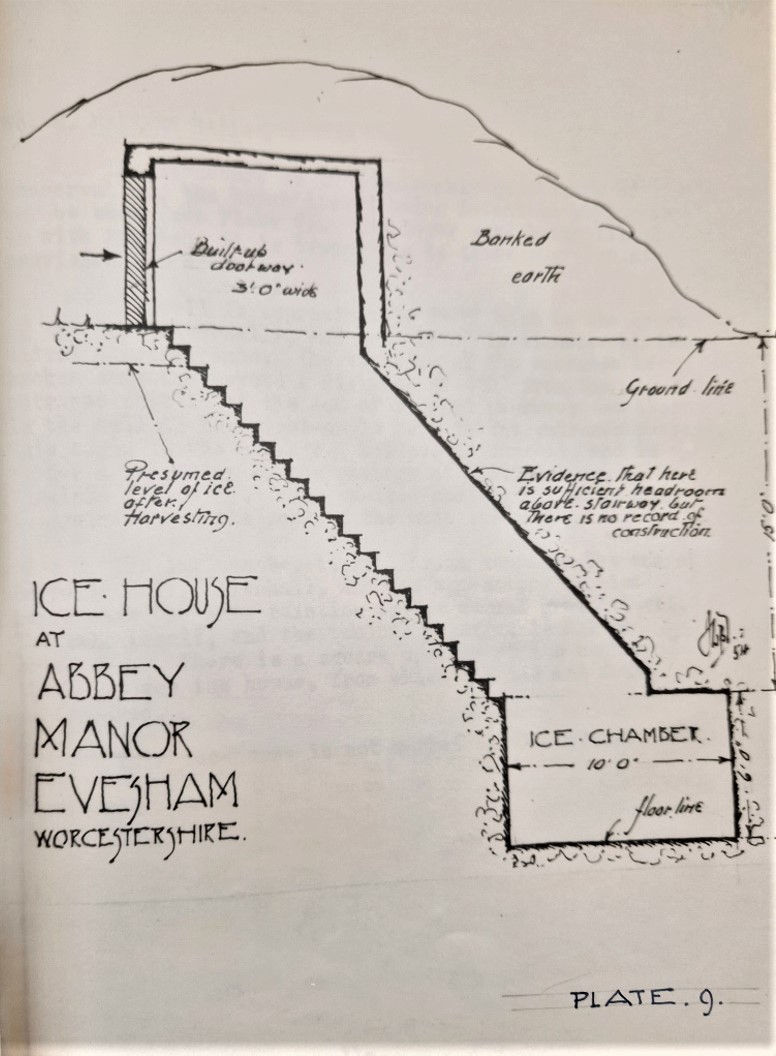

Sketch of the subterranean ice house at Abbey Manor, Evesham, Worcestershire / SPAB archive.

As well as preserving fish, meat and other fresh produce, ice houses meant that the well-heeled could now serve up chilled drinks to their guests on even the most sweltering summer days. And in some cases, even ice cream.

Can you imagine the gasps of astonishment as Charles II and his top table were served up Britain’s first ice cream (served with white strawberries) in 1672? A spectacle only made possible thanks to the ice house he commissioned at Green Park.

The rise and fall of ice houses

With refined construction techniques, ice houses had become a popular feature on large estates by the 18th century. The structure would be loaded up in winter with ice cut from nearby frozen lakes or ponds.

By the 19th century, an international ice trade was booming and industrial-scale ice houses were springing up, particularly for use by fish merchants. The ice itself was imported on straw-packed ships from Scandinavia and North America – where it was the second most lucrative export after cotton.

Of course, ice houses were made largely obsolete by the invention of the fridge. But being strong and subterranean, some found another life as air raid shelters in the 1940s. Many of these architectural curiosities still survive in the grounds of stately homes.

From the SPAB archive: Elmdon Hall, Solihull

Around 3,000 ice houses were built across Britain and of course not all survive. One such example from our archives is the ice house at Elmdon Hall which was in use until at least 1913 and unfortunately has since been demolished.

The account of it in Ice houses in the Midlands (SPAB archive) really brings to life the role that ice houses played, even into the early 20th Century.

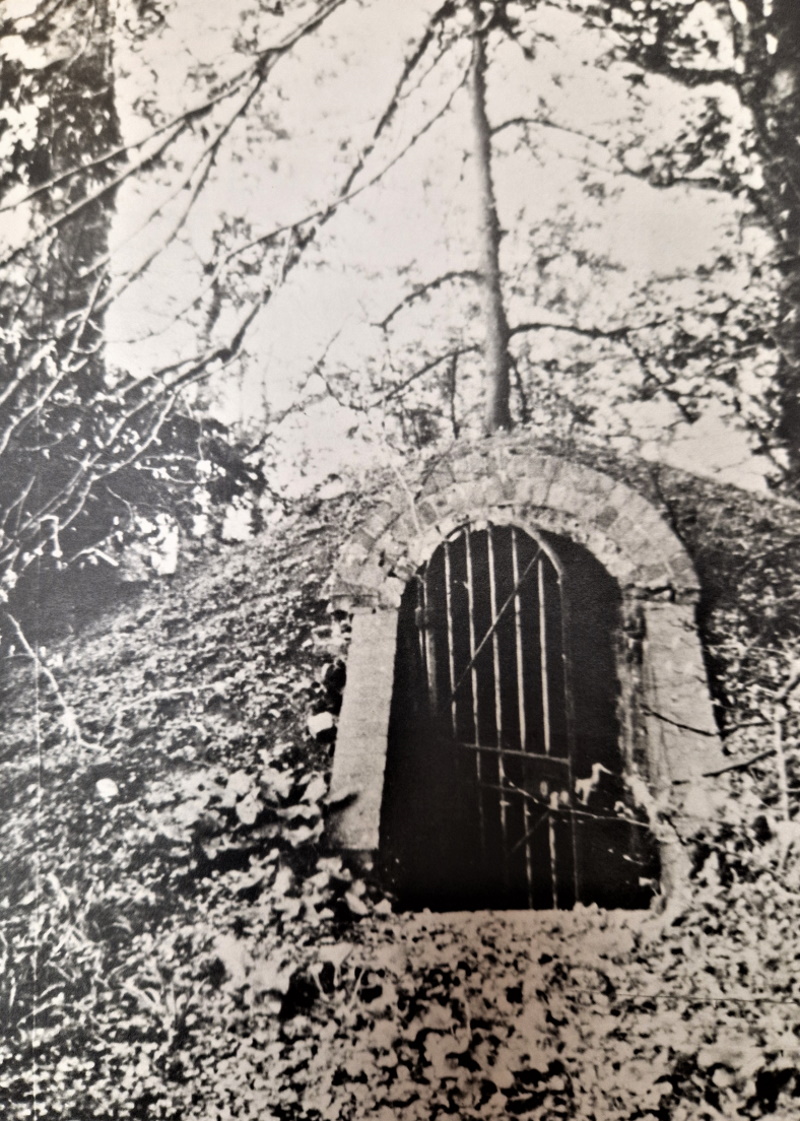

This ice house was similar in size and structure to the ice house at Barrells Hall in Warwickshire (pictured), although it was entirely underground, with access gained via two lids — one at ground level and one four or five feet below — with a ladder to descend into the icy depths. The road from the lake to the ice house had a steep incline, so a further climb to the top of an artificial mound may have been deemed impractical.

The ice house at Barrells Hall, Warwickshire, similar in shape and structure to that at Elmdon Hall / SPAB archive.

Ice was collected every winter from the lake and locals were employed to cart the ice up the steep slope to the well. The account tells us they were rewarded with a supper at the end of a hard day’s labour, which seems only fair given how strenuous the work would have been.

While many ice houses were used to store meat, drinks and other delicacies, this particular one was used to store fruit, including Williams pears, suspended in wooden boxes from the ceiling.

These treats were of course meant for the owners, but some of the gamekeepers couldn’t resist the temptation: “The ladder was advisedly removed but on occasion gamekeepers have been known to gain access and to sharpen a stick from the coppice to spear juicy pears from the access-lid of the well. Too often the pears were a little too juicy and slipped below into the ice.”

Mr Pratley, a local man employed at Elmdon Hall as a bird-boy in 1913, is quote indirectly in the archived pamphlet: ‘Mr Pratley could not tell me how long the ice lasted, but he said although there was no ventilation, the air inside was always sweet!”.

Unfortunately, many of Britain’s ice houses have fallen into disrepair or been demolished, although more exist than is perhaps realised. Another interesting part of our built heritage to be spotted out and about.