From the archive: Old London Bridge

Share on:

Dr David Harrison, of our London regional Group, looks to our archive to tell the story of SPAB's valiant, though ultimately unsuccessful attempts to save an arch of the iconic bridge which was uncovered in 1921.

A detail from an engraving by Claes Visscher showing Old London Bridge in 1616

The famous Old London Bridge, the longest inhabited bridge in Europe, was completed in 1209. For centuries people marvelled at the famous structure, but by the 18th century it had become unfashionable and appeared unsuitable for a modern city. In 1760 the houses were demolished, the bridge was widened and the two central arches were replaced by one.

London Bridge from Pepper Alley Stairs by Herbert Pugh, with the new "Great Arch" at the centre. Credit: Bank of England Museum.

Finally, the old bridge was demolished, and its replacement, John Rennie the Younger’s fine, plain, five-span structure was opened in 1831 (itself unnecessarily pulled down in the 1970s). Rennie’s bridge was upstream of its predecessor, and the different alignment meant a new approach had to be created. St Magnus the Martyr exchanged its separated churchyard to build the new streets in return for a new yard adjacent to the church, which included the northern approaches to the old bridge.

The Demolition of Old London Bridge, 1832 by J.W.S. Credit: Guildhall Gallery, London.

In 1921, during the construction of Adelaide House which stands in front of the St Magnus churchyard, the second arch from the north of the medieval bridge was uncovered. The find caused great excitement. SPAB, under its great Secretary A R Powys, sought valiantly to preserve the remains. Other organisations, such as the newly-formed London Society, the Concrete Institute and individuals added their support. The Archbishop of Canterbury himself presided over a public meeting on the issue. The developers offered to save the arch provided they received compensation between £6-10,000.

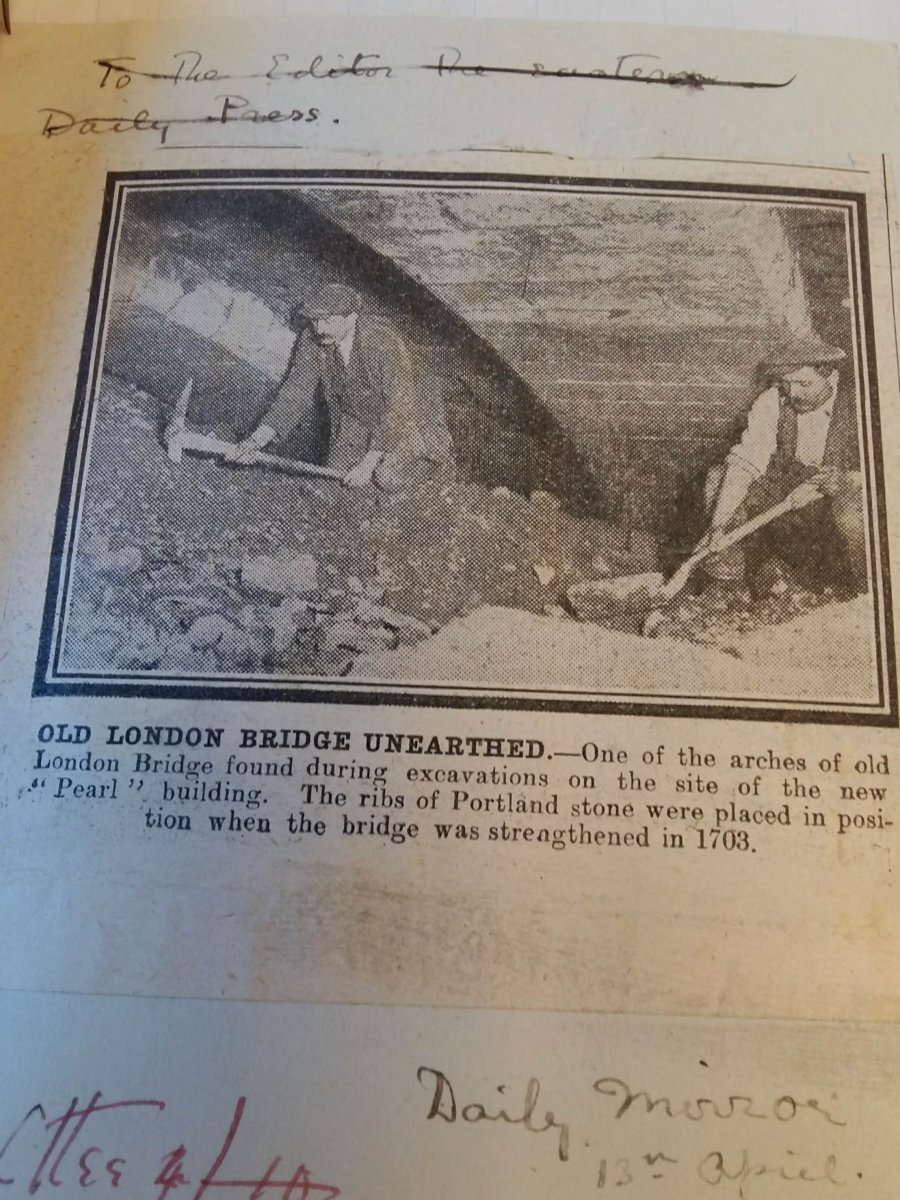

The arch found during construction of Adelaide House, April 1921, SPAB archive.

Alas, the preservationists received a negative response from the authorities. The Government claimed that the purchase could not be afforded. The Bridge House Estates Committee in the City of London, who own and maintain the bridge, decided they were unable to help. There was also opposition from the Society of Antiquaries. Hercules Read, their President, wrote to the Times, declaring 'my council felt very strongly that it would not be justified in making any appeal [for funds] to the general public'. Finally, on October 8 1921, The Observer reported that a delegation the following day would seek to persuade Sir Robert McAlpine to reprieve the arch. It failed and the arch was lost.

The forthcoming centenary of the discovery of the arch led me to the SPAB archives. It was evident that parts of the ancient structure were north and east of the Adelaide House. It seems likely that the northern abutment and possibly the first arch of the bridge lie at the southern end of the churchyard. SPAB London Group commissioned Dr Kevin Blockley to undertake a desk-based assessment to identify the precise location of the north end of the medieval bridge and set out a methodology for undertaking a small research excavation. Is it possible that a piece of London’s most iconic structure could finally be revealed and preserved for public enjoyment?

To hear more from David, join the SPAB London Group's virtual Walk to Nowhere, 1 July at 6.30 pm. Tickets are free, but donations are welcome. Dr Blockley’s report will be published on the SPAB website.

St Magnus the Martyr and Adelaide House from the Monument. Credit: Michael Cooper.

Sign up for our email newsletter

Get involved