Timber windows

The unnecessary replacement of old timber windows is of continuing concern to the SPAB. Such work can diminish both the character and value of an older building. Neighbouring properties could well suffer too.

Why are old timber windows worth keeping?

Old windows can contribute immeasurably to the special interest of a building. The timber used historically is superior to that widely available today. Compared to manufacture with modern substitute materials, use of timber is also more environmentally-friendly and facilitates easier repair. Substitutes are rarely as low-maintenance as often supposed – testified, for instance, by the marketing of purpose-made paint for PVCu windows discoloured by sunlight. Additionally, lower long-term costs favour the retention of old timber windows.

Is decay or a desire to double-glaze a good reason to replace an old timber window?

Usually not. Existing timber windows can often be repaired and, if necessary, upgraded for draught-proofing or better security. Some examples of basic repairs are outlined below; upgrading methods see Upgrading Windows. During any work, be careful to protect old glass and ironmongery against damage or loss.

Replacement is the last resort, and should be like-for-like in terms of style and materials. The SPAB may be able to advise on the names of joiners.

Decayed window

How do you repair a rotten timber window?

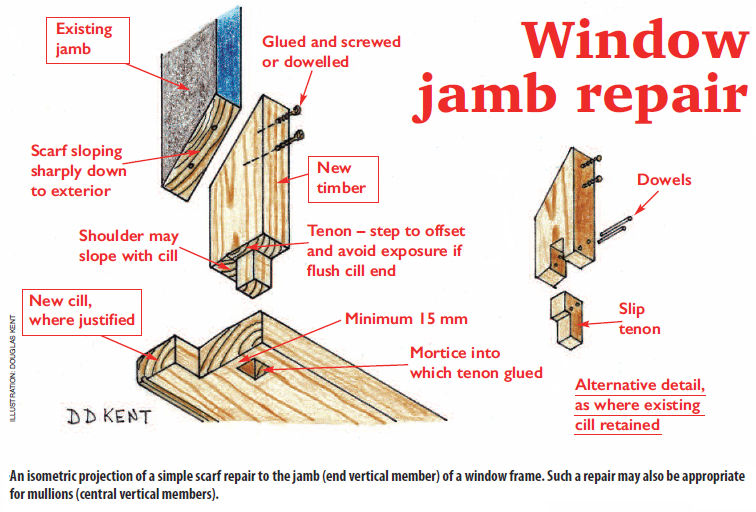

Commonly, only a small area is affected, such as the bottom of the window where there is wet rot. A skilled carpenter will in many cases be able to let in well-seasoned matching new timber. For example, a decayed end to a bottom rail might be renewed, complete with tenon, and the joint pegged, re-wedged and glued. A rotten outer section to a cill may be cut back in situ and replaced with new timber held by glue and non-ferrous screws. New timber of low natural durability should be double vacuum treated.

Minor areas of decay can simply be built up with two-pack filler. It is important, of course, to eliminate gutter leaks or other causes of damp.

How do you deal with loose joints in a timber window?

Joints can open due to the breakdown of glue and loose wedges. After removing the wedges, and perhaps some of the glass, it should be possible to reglue and re-wedge joints. Glue can be worked down the base of tenons with a hacksaw blade or piece of card.

How do you stop a timber window binding?

Where excess paint or wrongly painted parts is causing sticking, an inorganic solvent stripper can help. Where binding results from a distorted frame, carefully planing and sanding should prevent jamming. Severe distortion, may indicate structural problems (wall movement or failed lintel). Where sliding sashes stick, this may indicate the need for general overhaul. Easing should be avoided in damp weather or recently uninhabited buildings, as opening lights will free themselves when environmental conditions change.

What of old timber sashes in poor working order?

This is no reason for replacement. Sash windows can be overhauled, and there are good companies that specialise in this work. Overhaul may entail replacing sash cords, patch repairing worn stiles, refixing or renewing staff and parting beads, or adjusting weights and easing pulleys.

How should I go about redecorating an old timber window?

Windows post-dating the 18th century are usually of softwood and require regular redecoration for protection. After removal of loose or defective paint, exposed surfaces are rubbed down (using wet abrasion to minimise hazardous dust). Paint selection will depend upon such factors as the historical importance of the building and surviving finishes. Legislation allows the use of lead-based paint, with permission, on certain listed buildings (Grades I and II*, or in Scotland Grade A), although toxicity concerns mean that alternative finishes are often specified today.

Edwardian windows

With what do I fill gaps between an old timber window frame and wall?

Existing material should be matched. Lime mortar would normally be anticipated, frequently with an early mastic on top for water-resistance. Such mastic typically comprises a fillet of sand and boiled linseed oil. Crevices beneath the lime mortar were filled with rolled, wetted newspaper. Modern equivalents such as polysulfide sealant are unsuitable. They reduce vapour permeability.

English Heritage (2012) Timber, Practical Building Conservation, Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Ltd

English Heritage (2011) Glass, Practical Building Conservation, Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Ltd